Thinking about all the possible uses for this material, the group led by Pulickel Ajayan submerged it in water and discovered that the viscoelastic coating is self-healing.

In the first test, the team coated small slabs of common “mild steel” with the sulfur-selenium alloy and, with a plain piece of steel for control, sank both into seawater for a month. The coated steel showed no discoloration or other change, but the bare steel rusted significantly. The coating proved highly resistant to oxidation while submerged.

To test against sulfate-reducing bacteria, which are known to accelerate corrosion up to 90 times faster than abiotic attackers, coated and uncoated samples were exposed for 30 days to plankton and biofilms. The researchers calculated an “inhibition efficiency” for the coating of 99.99%.

The compound also performed well compared to commercial coatings with a similar thickness of about 100 microns, easily adhering to steel while warding off attackers.

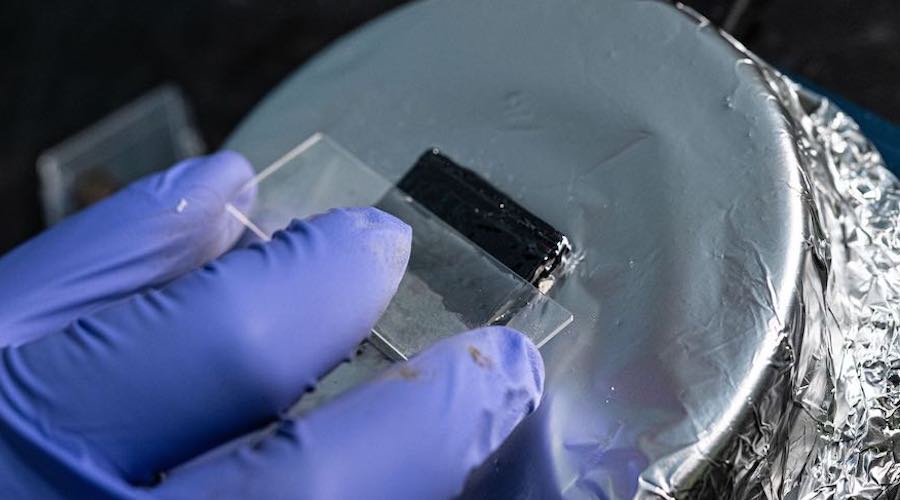

Finally, the team tested the alloy’s self-healing properties by cutting a film in half and placing the pieces next to each other on a hotplate. The separated parts reconnected into a single film in about two minutes when heated to about 70 degrees Celsius (158 degrees Fahrenheit) and could be folded just like the original film. Pinhole defects were healed by heating them at 130 C for 15 minutes.

Subsequent tests with the healed alloys proved their ability to protect steel just as well as pristine coatings.

The explanation for these behaviors lies in the fact that sulfur-selenium combines the best properties of inorganic coatings like zinc- and chromium-based compounds that bar moisture and chlorine ions but not sulfate-reducing biofilms, and polymer-based coatings that protect steel under abiotic conditions but are susceptible to microbe-induced corrosion.

According to Ajayan, these results suggest that the coating could be of use in infrastructure projects — buildings, bridges and anything above or below the water made of steel — that require protection from the elements.

“The first target is structures, but we’re aware the electronics industry faces some of the same problems with corrosion,” Ajayan said. “There are opportunities.”