The idea is that students and other people interested in the field of geology can blend virtual and in-person field trips.

“The UW Virtual Field Geology project has many goals: to make geology field experiences accessible to more people; to document geological field sites that may be at risk from erosion or development; to offer virtual ‘dry run’ experiences that complement field courses and help new students acclimate to the field, and to allow scientific collaborators to virtually visit a field site and explore it together,” the scientists said in a media statement.

Even though in most countries people can now travel and assemble, the team believes virtual experiences could become part of a “new normal” for geology research and education.

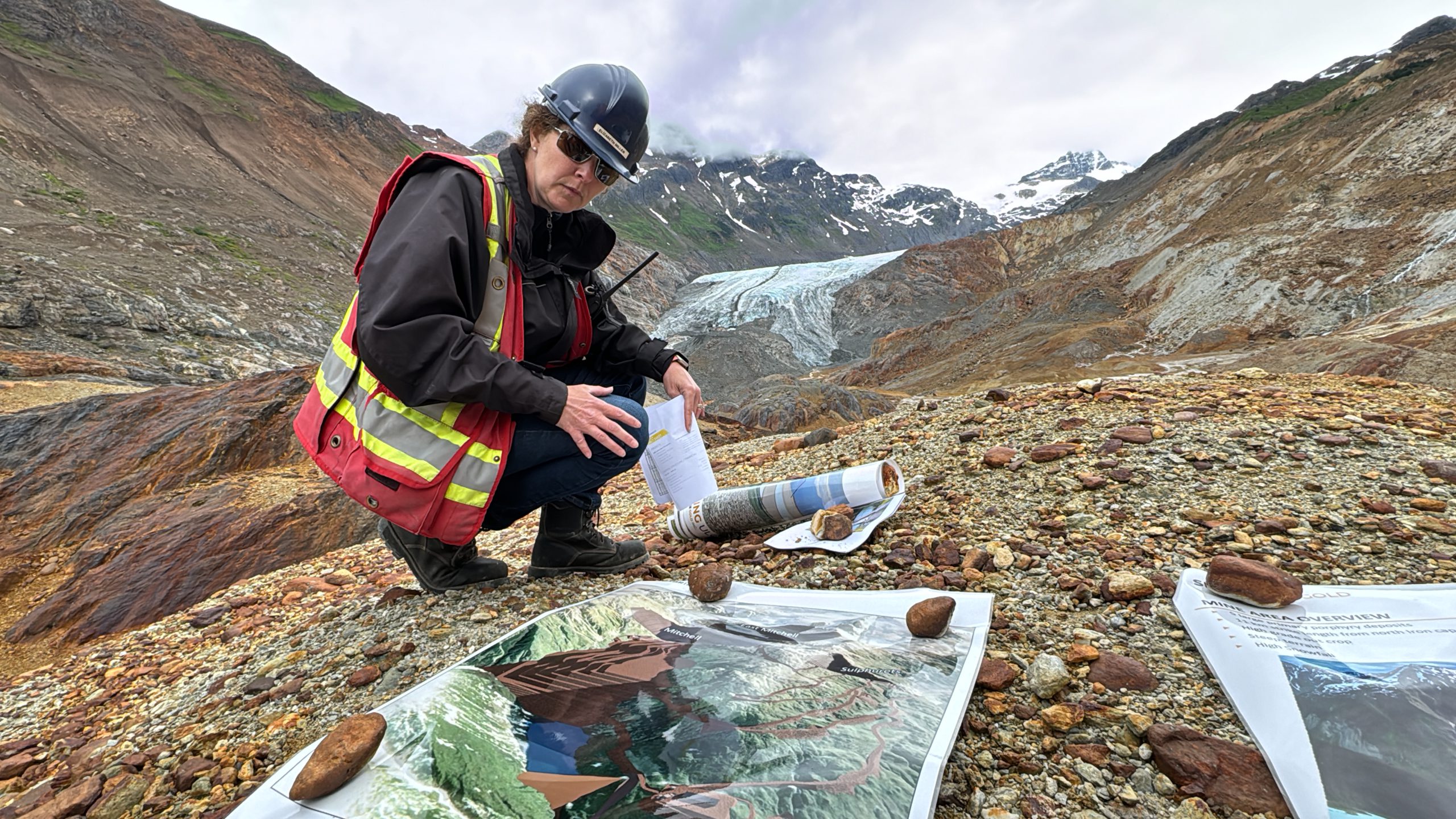

“Part of increasing access to the field is to help people know what to anticipate,” head researcher Juliet Crider said. “To the extent that we can help students anticipate both the outdoors experience and the science experience, then the uncertainty and maybe anxiety is reduced, and people can focus on the learning goals.”

The virtual experiences allow people to visit the field site and use common geology tools to measure angles in the rock layers or orientation of cracks that explain a landscape’s history. While a virtual option benefits anyone challenged by the travel and access to a remote field site, it also lets all students and researchers review techniques before reaching the actual location.

In the web-based virtual experience, keyboard commands let a user walk across the landscape. Users can try various tools to measure distances and angles. Selecting three points creates a virtual plane and displays its orientation. Data can be downloaded into a spreadsheet or directly into a popular geology software program.

“What’s unique about this experience is that it’s open-ended, which allows instructors to tailor the lessons and the goals,” Crider said. “Students decide what to measure, and where to measure, to answer the questions—it’s not predetermined. Making those decisions is an important thing to learn.”

Superhuman powers

The virtual experience also gives the scientist superhuman powers to instantly swoop from one place to another, and zoom in and out to explore a site at different scales.

“One of the cool advantages of the game is that you can fly. There’s a little jetpack icon and then you go up in the air, and all of a sudden your perspective changes, and you can travel quickly from place to place,” Max Needle, lead author of the study that presents the new technique, said.

It also provides access to sites that have limited or risky access. For example, at the Whaleback anticline, a lot of the curved rock geometry is exposed at a height of 30 feet, where it is very difficult to walk without risking fatality.

“As a teaching assistant, I’ve seen students confronted with challenges in the field that go beyond the academic aspect,” Needle said. “Or maybe someone can’t go into the field because they have bad asthma, or a particular field site can only be accessed with specialized climbing gear. We think a lot of people can benefit from these tools.”