One of the main issues with the EIA was related to the possibility that the gigantic tunnels needed for the mine could affect the quality and amount of water flowing from the páramo to the city of Bucaramanga’s metropolitan aqueduct, which supplies fresh water to about 2 million people.

This is because, if approved, the project would be surrounded by – although technically it would be outside of – a protected area covered with subalpine forests above the continuous tree line but below the permanent snow mark, where water is naturally stored during the rainy season and released during the dry season.

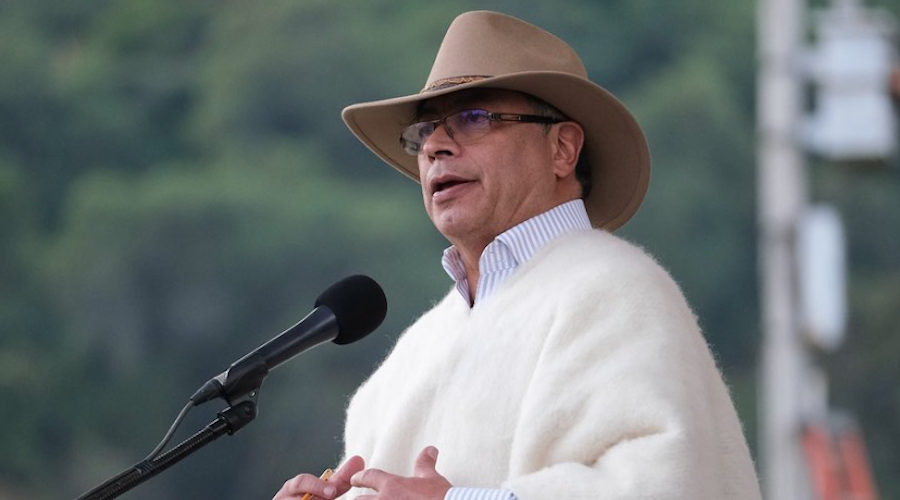

“The issue is the flow of the water, not the border of the páramo,” Petro said. “It is irrelevant for the city of Bucaramanga if the large gold mine is established above or below the páramo’s border if the water is affected anyway.”

The town hall with the paramo communities took place following a January blockade carried out by Santander’s farmers and small business owners who were protesting the impacts the possibility of displacement due to the new boundaries proposed by the legislative power in the Santurbán area when the $1.2-billion Soto Norte project was first presented.

After noting that when he was a senator he said that such an idea was a “trap,” Petro ended up telling the people gathered last Friday, that Santurbán and its water belong to them.

“After hearing from you that there is a displacement process or the risk or threat of displacement of farmers in the area, who have always lived there, it becomes clear to me that wherever big mining sets up shop, people end up displaced,” the president said. “I will not allow displacements in the Colombian páramos.”