Published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, the study focused on what happened at the Tambopata National Reserve in the 2001 to 2014 period.

During this time frame, demand for gold rose, roads penetrated the region and mining surged. In parallel, mining-related deforestation rose by almost 100,000 acres.

Also in this period, local agencies issued provisional titles to miners to conduct their operations safely. After receiving a provisional title, miners would, in theory, undergo a series of environmental impact and compliance assessments before they started work.

However, the researchers noticed that the regulation process took a long time and, thus, many miners simply took their provisional title as a green light to start mining, and never went through with the environmental impact assessments.

In fact, in those 13 years, no mining operations made it through the full compliance process, and as such the researchers found little evidence for improved environmental outcomes in formalized mining areas.

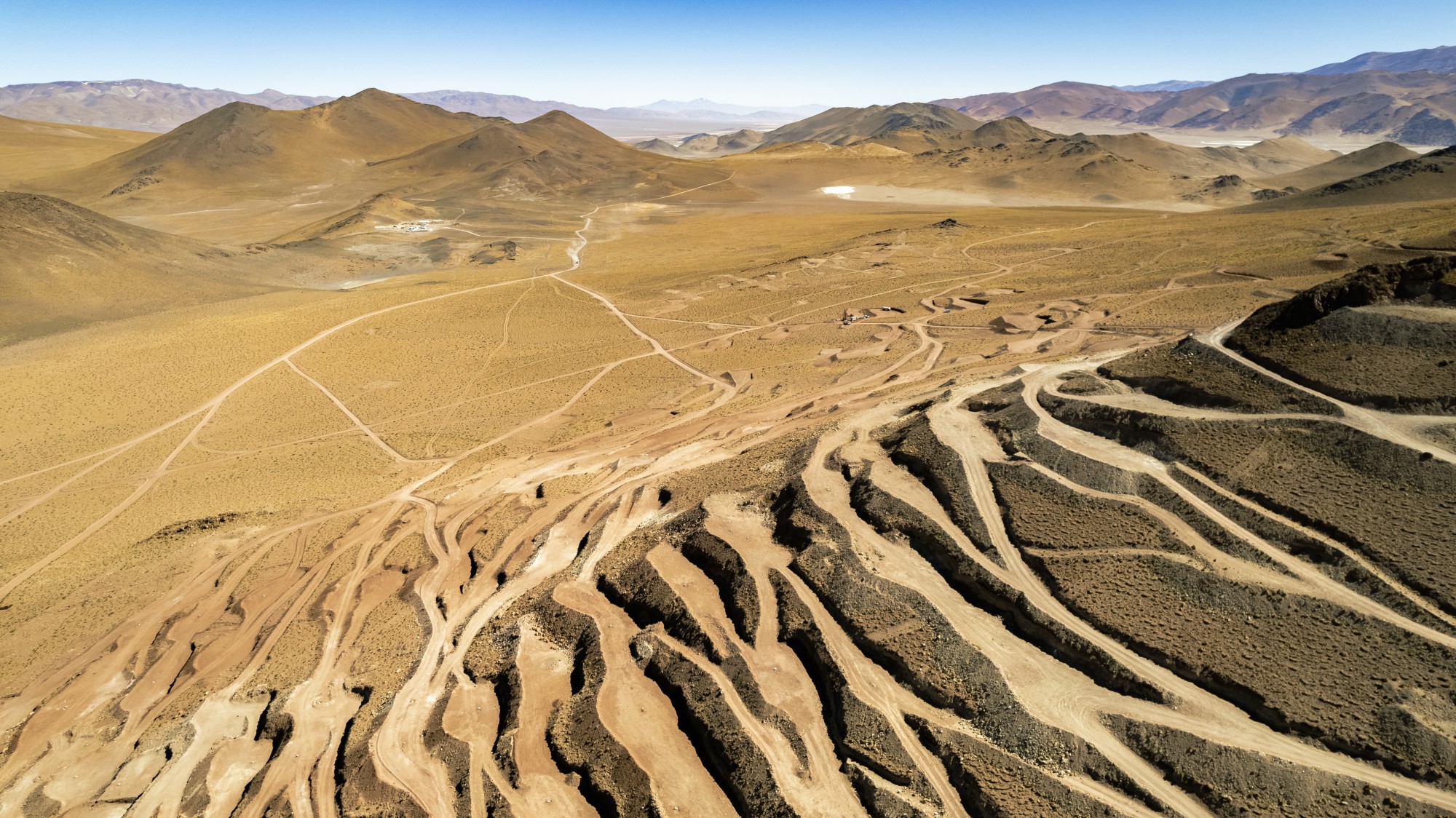

To assess those environmental outcomes, the team used satellite imagery analysis to see how much of the forest had been cut down, as compared to areas without formalized mining regulations.

After looking at the differences, the group concluded that while formalizing mining has the potential to decrease environmental damage, it needs enforcement and regulations that match the local context.

“To sort out in a fair way who owns what land, with what rights, that is a slow process,” Lisa Naughton, coauthor of the study, said in a media statement. “[But] this gold rush is explosive. By the time you have well-regulated and transparent public land and property rights, the forest will be gone.”

According to Naughton, many members of the community at Tambopata are aware of the problems with mining formalization but have not had a chance to systematically study the environmental consequences.

Now, the researcher and her co-authors hope their study will set a precedent for monitoring formalization interventions in Tambopata and other tropical sites in Colombia, Brazil and Bolivia, which are losing forest to mining.