Such a representation tells the story of changing environments, the development of a habitable biosphere, the evolution of continents, and the accumulation of mineral resources at ancient plate boundaries.

“This new approach allows a greater understanding of the nature of ancient geology in order to reconstruct the arrangement and movement of tectonic plates on Earth through time,” Barham said in a media statement. “The world’s beaches faithfully record a detailed history of our planet’s geological past, with billions of years of earth’s history imprinted in the geology of each grain of sand and our technique helps unlock this information.”

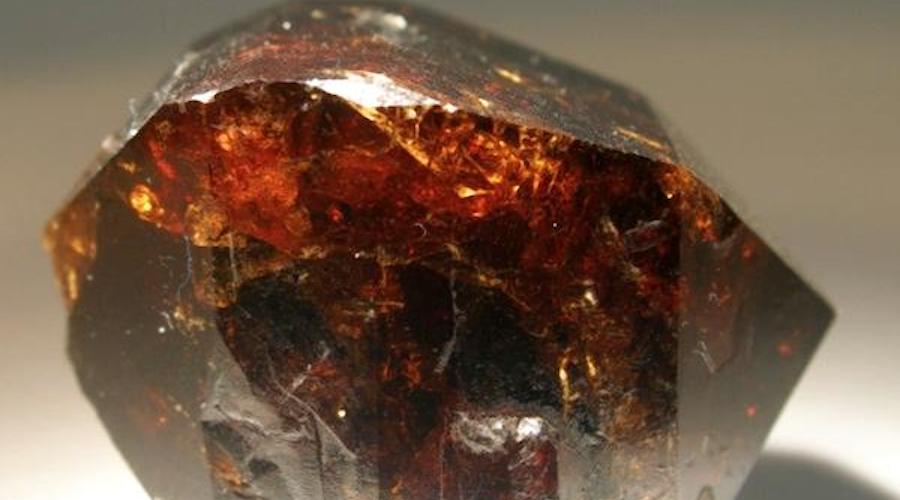

In a paper published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Barham and his colleague Chris Kirkland explain that zircons contain chemical elements that allow to date and reconstruct the conditions of mineral formation.

“Much like human population demographics traces the evolution of countries, this technique allows us to chart the evolution of continents by identifying the particular age population demographics of zircon grains in a sediment,” Kirkland said.

The researcher pointed out that the way the planet recycles itself through erosion is tracked in the pattern of ages of zircon grains in different geological settings.

“For example, the sediment on the west and east coasts of South America is completely different because there are many young grains on the west side that were created from crust plunging beneath the continent, driving earthquakes and volcanoes in the Andes. Whereas on the east coast, all is relatively calm geologically and there is a mix of old and young grains picked up from a diversity of rocks across the Amazon basin,” Kirkland said.