In Huang’s view, his team’s proposal could save billions of dollars around the world by minimizing the cost and risk of tailings storage.

Using the Canadian Light Source (CLS) at the University of Saskatchewan to determine the underlying mechanisms of soil formation, the group found a way to accelerate natural soil processes to convert tailings into healthy soil.

“Tailings have no biologically friendly properties for growing plants. Roots and water cannot penetrate them, and soluble salts and metals in tailings can kill plants and soil microbes,” Huang said. “If you wait for nature to slowly weather the tailings and turn them into soil, it could take a couple thousand years.”

He and his colleagues, thus, decided to convert colossal volumes of biologically hostile tailings into growth media similar to natural soil by developing a soil structure that would enable the biological activity of microbes and plants, virtually establishing a natural ecosystem.

The process involves encouraging specific microbes to grow in tailings that have been amended with plant mulch from agricultural waste and urban green waste. These microbes “eat” the organics and minerals in tailings, transforming them into functional aggregates or soil crumbs, the building blocks of healthy soil.

“You have microbially active surfaces in soil crumbs that develop a porosity in compacted tailings that allows the gas, water, roots, and microbes to survive, just like in arable soil,” Huang said. “Therefore, the dead mineral matrix of tailings becomes a soil-like media that will enable plants to grow.”

Huang noted that this process—which can occur in as little as 12 months—can also be used to restore soils damaged by over-farming, overuse of fertilizers, and climate change.

Using the CLS’s synchrotron light the scientists were able to visualize the detailed mechanism of how they developed the organic-mineral interfaces and revitalize the tailings.

“We needed to use the SM beamline to unravel at the nanometer scale the immediate interfaces and how the minerals change, and how they interact with organics,” Huang said. “The facility access and the expert inputs of the beamline staff were critical to enable us to collect quality data and therefore to have reliable scientific evidence.”

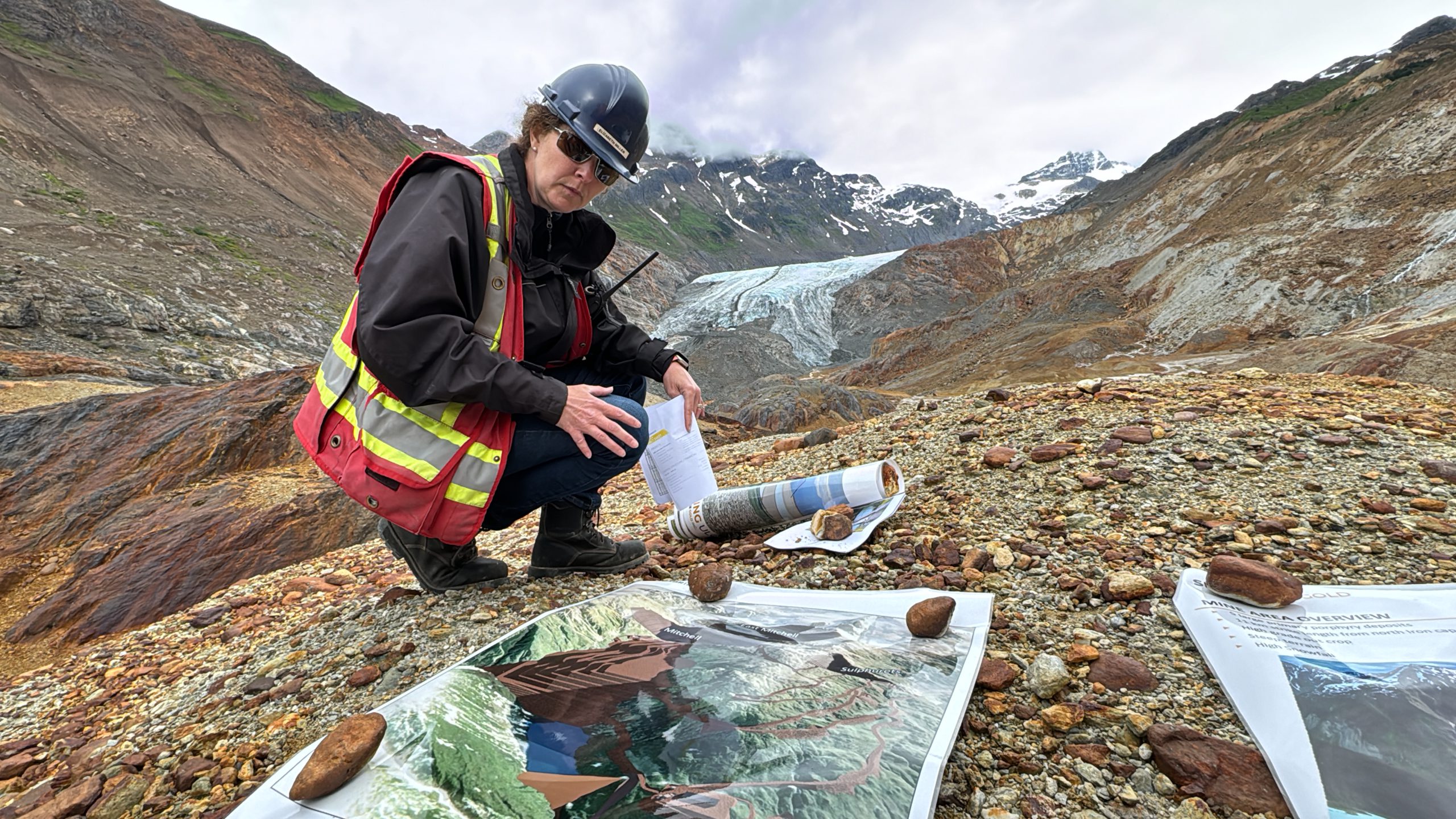

The team has also completed a field trial and an extensive greenhouse trial using the rehabilitated tailings to grow crops and native plants.

“We are confident that it works. The maize and sorghum love it,” Huang noted. “The technology is usable now. Someone just needs to use it at mine sites.”