In a presentation at the Goldschmidt Conference, research lead Michael Broadly, from the University of Lorraine, explained that volatiles such as hydrogen, nitrogen, neon, and carbon-bearing species are light chemical elements and compounds that can be readily vaporized due to heat or pressure changes. Yet, they are necessary for life, especially carbon and nitrogen.

On Earth, volatile substances mostly bubble up from the inside of the planet and are brought to the surface through such things as volcanic eruptions.

According to Broadly, knowing when the volatiles arrived in the Earth’s atmosphere is key to understanding when the conditions were suitable for the origin and development of life, but until now there has been no way of understanding these conditions in the deep past.

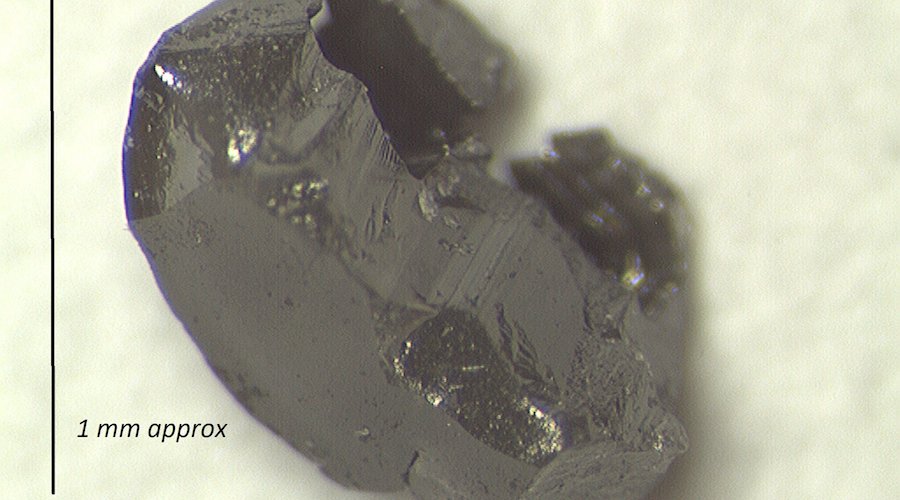

“Studying the composition of the Earth’s modern mantle is relatively simple. On average the mantle layer begins around 30 kilometers below the Earth’s surface, and so we can collect samples thrown up by volcanoes and study the fluids and gases trapped inside,” the scientist said. “However, the constant churning of the Earth’s crust via plate tectonics means that older samples have mostly been destroyed. Diamonds however are comparatively indestructible, they’re ideal time capsules.”

The rare, fibrous diamonds studied by the researcher and his team were trapped in 2.7-billion-year-old highly preserved rock from Wawa, on Lake Superior in Canada.

To analyze their composition, the group heated them to over 2000 degrees Celsius to transform them into graphite, which then released tiny quantities of gas for measurement.

The team then measured the isotopes of helium, neon, and argon, and found that they were present in similar proportions to those found in the upper mantle today. This is what allowed them to conclude that there has probably been little change in the proportion of volatiles generally and that the distribution of essential volatile elements between the mantle and the atmosphere is likely to have remained fairly stable throughout most of Earth’s life. The mantle is the part between the Earth’s crust and the core, and it comprises around 84% of the planet’s volume.

“This was a surprising result. It means the volatile-rich environment we see around us today is not a recent development,” Broadly said. “Our work shows that these conditions were present at least 2.7 billion years ago, but the diamonds we use may be much older, so it’s likely that these conditions were set well before our 2.7 billion year threshold.”