Like the vast majority of the mining industry in Canada, Agnico Eagle is targeting net zero by 2050, with an interim goal to reduce its Scope 1 and 2 emissions — which cover both direct emissions and emissions from the energy sources it uses, such as diesel — by 30% before 2030.

“Dependence on fossil fuels to fulfill energy requirements and the associated high costs are indeed challenging,” Adam Grzegorczyk, sustainability manager at Agnico Eagle, said in an email.

Agnico Eagle isn’t alone in its diesel dependence. Baffinland Iron Mines Corp. runs the Mary River iron ore mine on Baffin Island. Rio Tinto (ASX: RIO; NYSE: RIO) and Dominion Diamond Mines jointly operate the Diavik Diamond Mine in the Northwest Territories, alongside Burgundy Diamond Mines (ASX: BDM), which owns the nearby Ekati diamond mine. Glencore Canada manages the Raglan nickel-copper mine in Nunavik, northern Quebec.

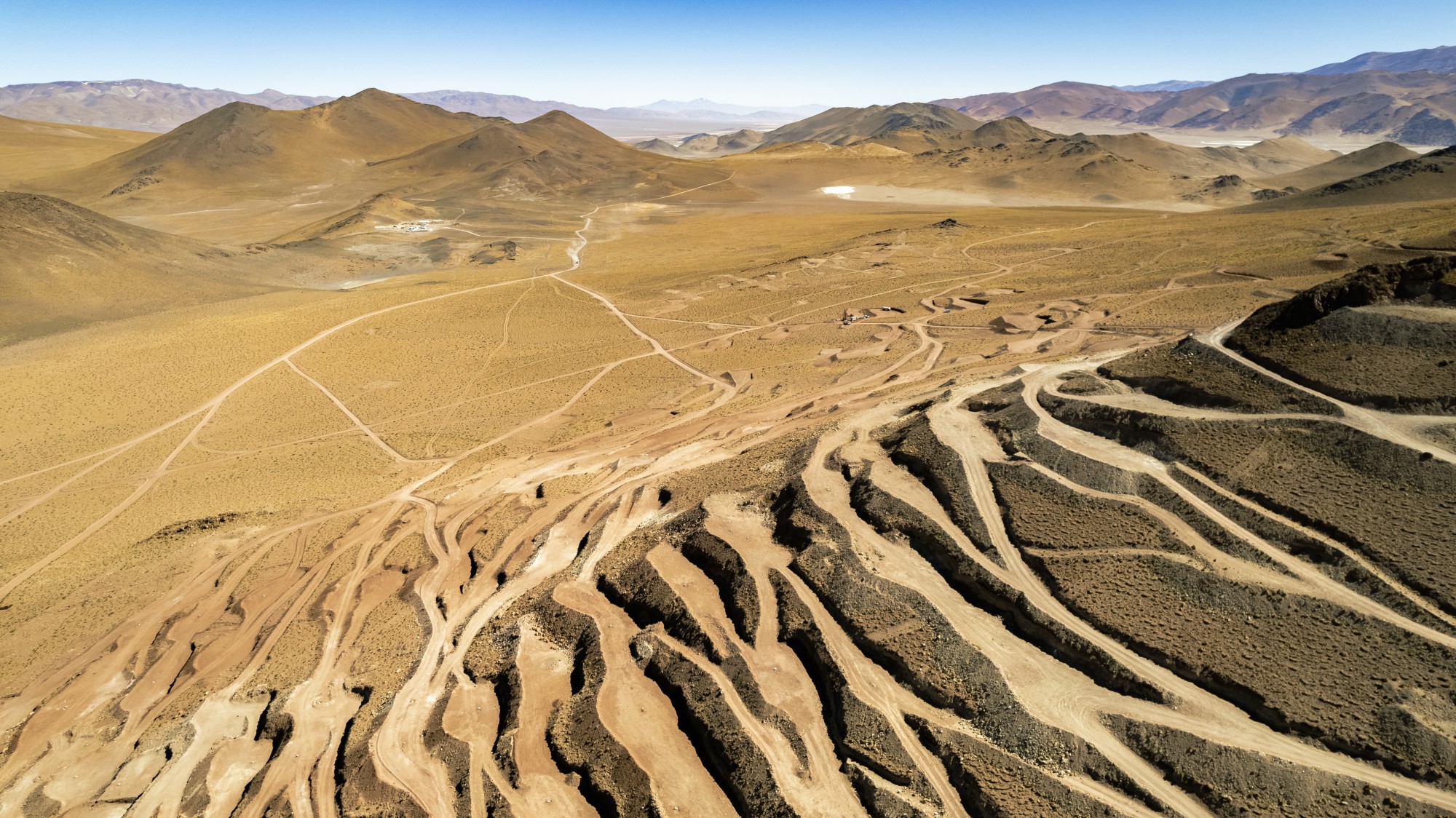

Despite growing pressure to decarbonize, mining projects in Canada’s Far North remain heavily reliant on diesel, often trucked in or flown to remote sites at great expense. The region’s extreme isolation, harsh climate, and lack of grid infrastructure make diesel the only viable option for generating heat and electricity year-round. While solar and wind offer promise, their intermittent output and high installation costs limit adoption.

Reliable source

Both Nunavut and the Northwest Territories have proposed transmission lines to bring clean energy to the regions. The $3.2-billion Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link transmission line would connect five Kivalliq communities and Agnico Eagle’s Meadowbank and Meliadine mines to Manitoba’s hydroelectric grid. The Taltson Hydro Expansion in the Northwest Territories is a $3-billion extension connecting communities and Diavik and Ekati to hydroelectric power.

Part of the impetus for these transmission investments is attracting future mines, Heather Exner-Pirot, director of the Natural Resources, Energy and Environment program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Ottawa, said by phone.

“If you’re a big international company like BHP (NYSE, LSE, ASX: BHP) or Rio Tinto (NYSE, LSE, ASX: RIO) and you have those ESG goals, you’re probably not going to build another diesel-dependent mine again,” Exner-Pirot said in an interview. “So that puts us at a disadvantage to a lot of places.”

But when it comes to net-zero goals for existing mines in the Far North, without the development of transmission lines, the projects need to tackle their diesel dependence incrementally through localized solutions.

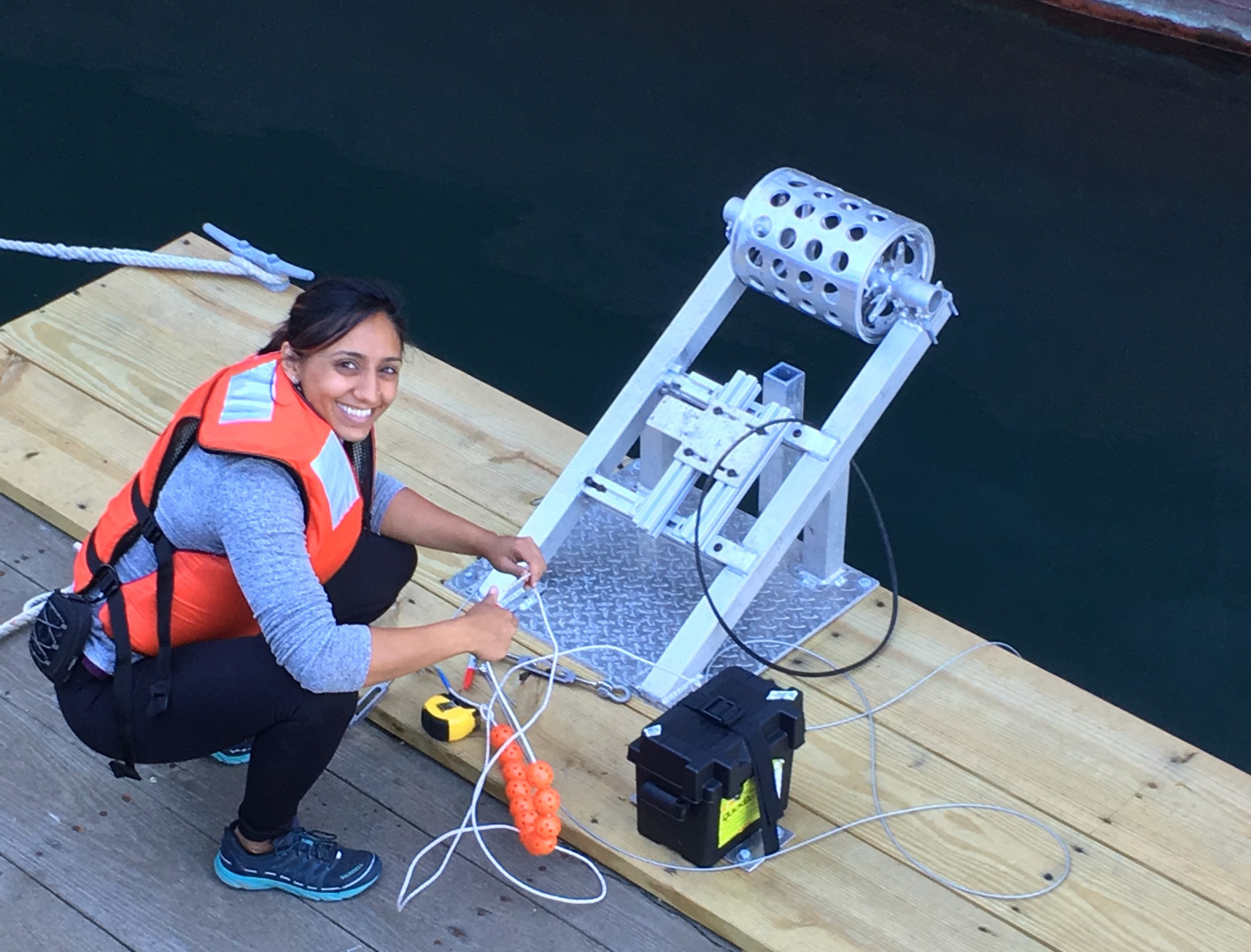

Ali Madiseh, an expert on sustainable mine energy systems at UBC’s Bradshaw Research Institute for Minerals and Mining (BRIMM), said there’s no single solution to decarbonization. “There’s a very diverse array of technologies that you have to implement.”

He points to trolley assist lines that reduce energy consumption and battery-powered trucks for underground operations. “The challenges in mining are gigantic and a lot of the time it’s not even technical challenges,” Madiseh said in an interview.

“Timing, availability, productivity, all that weaves into the economics and then you suddenly find that you’re financing a mine and you’re not willing to take another $400 million loan just to show that you’re electric.”

Individual solutions

Agnico Eagle is approaching decarbonization through energy efficiency initiatives, technology transition and increased use of renewable energy. In April, the company signed a power purchase agreement with Kitikmeot Tugliq Limited Partnership to launch a wind energy project at the company’s Hope Bay site to reduce diesel dependence.

“At our Meliadine mine in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, we have introduced ultra-efficient generators and a heat recovery system to capture and repurpose waste heat,” Grzegorczyk, Agnico Eagle’s sustainability manager, said.

This process includes periodic audits on the performance of the systems to ensure efficiency, not only at installation but throughout their operational lifespan. “This has reduced diesel consumption by an estimated 4.5 million litres annually since 2018, which would avoid roughly 12,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions per year,” Grzegorczyk said.

Last July, Rio Tinto completed the installation of a solar plant at its Diavik diamond mine, which is expected to reduce diesel consumption by one million litres per year and cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2,900 tonnes of CO2 equivalent. The solar plant will supply up to 25% of Diavik’s electricity as the mine decommissions over the next four years. Diavik also hosts the largest wind power plant in Canada’s Far North.

Exner-Pirot said there’s growing interest in small modular reactors (SMRs) as a solution to the North’s clean energy woes. “Remote mines are almost a perfect application for the technology.”

Natural Resources Canada estimates the cost of a mining suitable SMR to be around $200 million to $250 million.

“In 10 years, that will be a great solution, but it’s not a solution today,” Exner-Pirot said. “Diesel is the solution.”