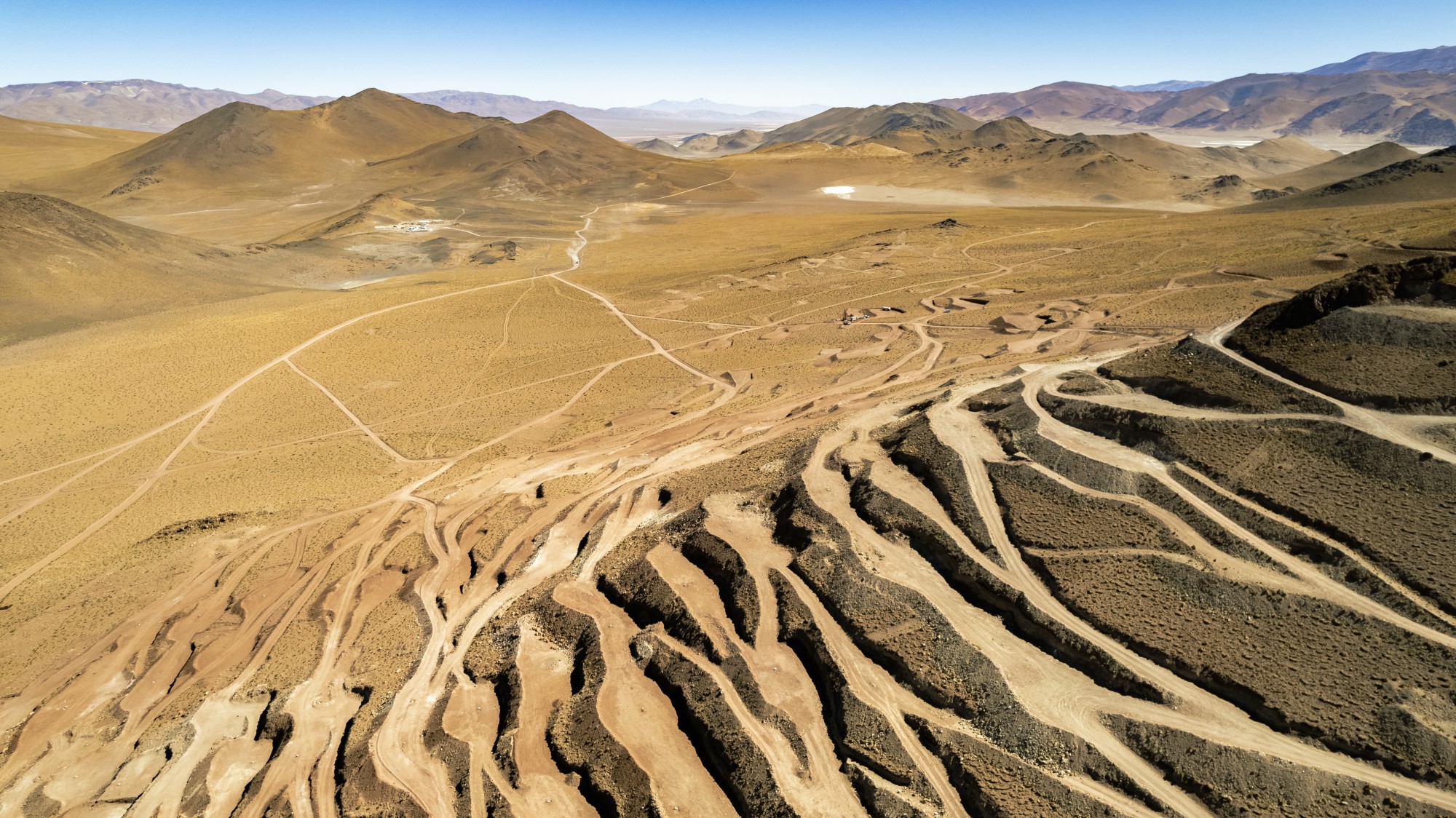

As an example, they mention that their methodology shows that total water usage in Chile’s Atacama salt flat is exceeding its resupply but the impact of lithium mining itself is comparatively small, as the extraction of the battery metal accounts for less than 10% of freshwater usage and its brine extraction does not correlate with changes in either surface-water features or basin-water storage.

“To understand the environmental effect of lithium mining, we need to understand the hydrology in the region the lithium is found. That hydrology is much more complex than previous researchers have given it credit for,” Brendan Moran, a postdoctoral research associate at UMass Amherst and the lead author of the paper, said in a media statement.

To illustrate the complexity, and the previous misconception about the Atacama salt flat’s hydrology, Moran and one of his co-authors David Boutt draw on the metaphor of a bank account.

Incorrect assumptions

“Imagine that you get a paycheck every month; when you go to balance your chequebook, as long as your monthly expenditures don’t exceed your monthly income, you are financially sustainable,” they said. “Previous studies of the Salar de Atacama have assumed that the infrequent rainfall and seasonal runoff from the mountain ranges that ring it were solely responsible for the water levels in the salt flats, but it turns out that assumption is incorrect.”

Using a variety of water tracers that can track the path that water takes on its way to salt flat, as well as the average age of water within different water bodies, including surface waters and sub-surface aquifers, Moran and his colleagues discovered that though localized, recent rainfall is critically important, more than half of the freshwater feeding the wetlands and lagoons is at least 60 years old.

“Because these regions are so dry, and the groundwater so old, the overall hydrological system responds very slowly to changes in climate, hydrology and water usage,” the researcher said. “At the same time, short-term climate changes, such as the recent major drought and extreme precipitation events, can cause substantial and rapid changes to the surface water and the fragile habitats they sustain.”

The impact of climate change

In the scientist’s view, given that climate change is likely to cause more severe droughts over the region, it could further stress the area’s water budget.

“To return to the accounting metaphor, the paycheck is likely getting smaller and isn’t coming monthly, but over a period of at least 60 years, which means that researchers need to be monitoring water usage on a much longer time scale than they currently do, while also paying attention to major events, like droughts, in the region,” Moran and Boutt said.

In addition to the geochemical tracers, the researchers performed their monitoring by looking at water usage data from the Chilean government and satellite imagery, which allowed them to assess the changing extent of wetlands over the past 40 years, rain gauges, and satellite measurements to determine changes in precipitation over the same period.

“Given how long it takes for groundwater to move within the basin, the effects of water over-use may still be making their way through the system and need to be closely monitored,” Moran said. “Potential impacts could last decades into the future.”