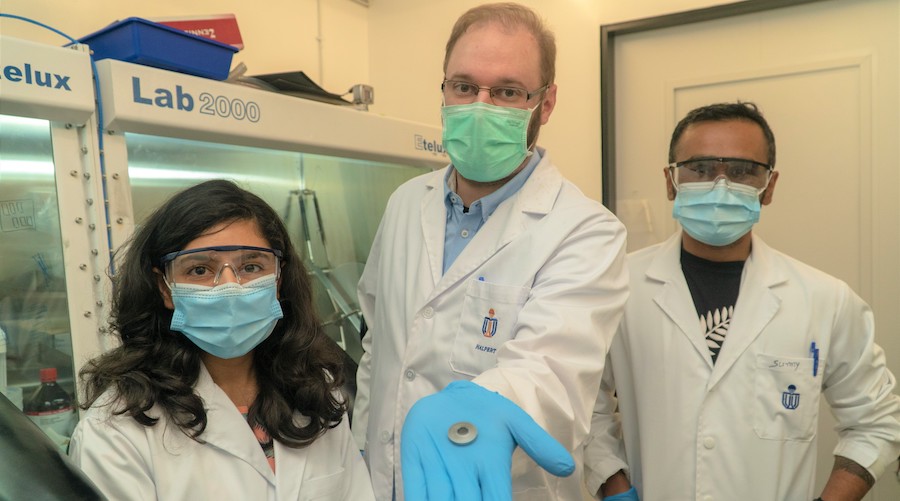

To address these challenges, the HKUST team led by Jonathan Eugene Halpert decided to expand the utility of perovskite, which has had applications in solar cells and most recently in batteries.

In detail, the team developed a perovskite halide that acts as a photo-electrode that can harvest energy under illumination without the assistance of an external load in a lithium-ion battery. This is in stark contrast with its existing counterpart for it does not contain lead, hence it has higher stability in air and is free from the concerns of metal poisoning. For their research, the team has replaced lead with bismuth, a non-toxic element, thus forming a strongly light-absorbing crystalline material.

In a paper published in the journal Nano Letters, the group explains that the lithium-ion battery works by allowing electrons to move from a high-energy state to a lower one while doing work in an external circuit. The photo battery, on the other hand, has a mechanism similar to an ordinary battery except that it need not be supplied current or plugged into the wall to be charged electrically, but can be charged photoelectrically under the sunlight. The active material is the perovskite which, when put under light, absorbs a photon and generates a pair of charges, known as an electron and a hole.

To back their proposal, the team conducted chrono-amperometry experiments under light and in the dark to analyze the increase in charging current caused by the light; they recorded a photo-conversion efficiency rate of 0.428% on photo-charging the battery after the first discharge.

“At present, we plug all our appliances into the wall to charge them. With further development in this field of photo-batteries, we might not have to plug them in at all in the future,” Halpert said in a media statement. “We might be able to harvest solar energy and use it to fulfil the power requirements of any devices with modest power needs. Our work is one of the initial steps taken in this field, and, of course, a lot of improvements will be needed to achieve better performance, but we are confident that we can improve its stability and average efficiency with further refinement.”

According to Halpert, his lab’s photo battery can serve as the built-in battery for devices such as smartphones or tablets, and even remote energy storage applications.

The next steps are, thus, to experiment with different materials for better performance and efficiency, so that the photo battery can be commercialized in the market.